“At one end of the spectrum there are issues and problems that are exclusively racial. Uniquely racial. At the opposite end of the spectrum, there are problems and issues which are uniquely sexual, but in the middle, they tend to overlap, there tend to be problems that are common to both groups.”1 – Pauli Murray

Civil Rights Activism

Segregation was obvious to Murray growing up in Durham as African Americans and whites were separated under Jim Crow laws. Signs to demonstrate segregation, like the one pictured above, were commonplace during her childhood.

From a young age, Pauli Murray was aware of being a minority. She remembers a sense of “loyalty and dedication to the advancement of the race,” and segregation being an institutionalized part of life growing up in North Carolina. She hated the segregation that she experienced in Durham, and took the opportunity to escape it when she moved to New York for her undergraduate degree at Hunter College.2

In 1938, Murray encountered racial discrimination when she applied for admission at the University of North Carolina Law School and was denied on the basis of race. Her case gained national attention as she challenged the policy.3 Murray approached the NAACP for support, however the NAACP could not take her case for two reasons. To begin with, after living in New York for college, she was technically no longer a North Carolina resident. Secondly, the NAACP was in a high profile position and would only take cases that they could be sure they would win in the national spotlight.4 Although Pauli Murray was unsuccessful in getting her rejection overturned, she challenged racial norms and demonstrated her commitment to Civil Rights by pushing back against racial discrimination.

Following Pauli Murray’s rejection from UNC, she demonstrated Civil Rights activism again in 1940 when she was charged with public disturbance and violating segregation law for refusing to move further back to in the “Negro” section of a Greyhound bus in Petersburg, Virginia. The state withdrew the segregation charge for political reasons, but fined Murray after convicting her of public disturbance. On principle, Murray endured jail time rather than pay the fine outright.5

Other Civil Rights activism can be noted through Pauli Murray’s affiliations, jobs, demonstrations, and publications. She was affiliated with the NAACP and CORE, worked on legal cases to fight discrimination, participated in sit-ins, and wrote books, articles, and poems that showed the injustices of segregation.6 Experiences with racial discrimination motivated Murray’s entrance into Howard Law School so that she could fight segregation at a legal level, and she explains that she concentrated her activism on race and civil rights until that point. However, when Murray experienced gender discrimination in law school, she also started to take interest in the women’s rights agenda.7

Other Civil Rights activism can be noted through Pauli Murray’s affiliations, jobs, demonstrations, and publications. She was affiliated with the NAACP and CORE, worked on legal cases to fight discrimination, participated in sit-ins, and wrote books, articles, and poems that showed the injustices of segregation.6 Experiences with racial discrimination motivated Murray’s entrance into Howard Law School so that she could fight segregation at a legal level, and she explains that she concentrated her activism on race and civil rights until that point. However, when Murray experienced gender discrimination in law school, she also started to take interest in the women’s rights agenda.7

Fighting for Women’s Rights

In her oral history, Pauli Murray explains her naiveté to gender discrimination, saying that she had only considered racial prejudices until law school where she also realized gender inequality. While studying law at Howard Law, Murray encountered explicit sexism; she was one of two females in the entire school, and was excluded from certain male advantages, like informal networking with professors. In addition, although she graduated first in her class, Murray was denied the usual reward of a fellowship to study at Harvard University, because Harvard was exclusively male. Murray notes that since Howard University was entirely African-American, sexism was isolated from racism. Thus, she pinpoints law school as the beginning of her conscious feminism.8

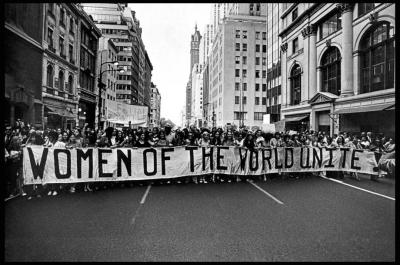

Pauli Murray went on to become an ardent feminist in addition to being a champion for racial equality. Her involvement in the women’s rights movement began in 1961 when she was appointed to the President’s Commission on the Status of Women Committee on Civil and Political Rights where “she helped bridge the decades-old conflict among women activists over the Equal Rights Amendment.”9 She also authored multiple articles to showcase the parallels between racism and sexism, including “Jane Crow and the Law: Discrimination and Title VII,” and “The Liberation of Black Women.” Her key argument in both articles was that permanent characteristics like sex and race place an individual into a caste at birth, and that the only remedy to this discrimination is societal change.10

Pauli Murray went on to become an ardent feminist in addition to being a champion for racial equality. Her involvement in the women’s rights movement began in 1961 when she was appointed to the President’s Commission on the Status of Women Committee on Civil and Political Rights where “she helped bridge the decades-old conflict among women activists over the Equal Rights Amendment.”9 She also authored multiple articles to showcase the parallels between racism and sexism, including “Jane Crow and the Law: Discrimination and Title VII,” and “The Liberation of Black Women.” Her key argument in both articles was that permanent characteristics like sex and race place an individual into a caste at birth, and that the only remedy to this discrimination is societal change.10

Pauli Murray was also one of the founders of National Organization for Women (NOW), along with other recognized feminists including Betty Friedan. However, she channeled most of her feminist energy into religious organizations and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), where she influenced the decision to establish a Women’s Rights Project. Overall, Pauli Murray saw the potential for an alliance between the Civil Rights and the women’s movements, and used her experience as an African-American woman to enhance both agendas.11

Pauli Murray was also one of the founders of National Organization for Women (NOW), along with other recognized feminists including Betty Friedan. However, she channeled most of her feminist energy into religious organizations and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), where she influenced the decision to establish a Women’s Rights Project. Overall, Pauli Murray saw the potential for an alliance between the Civil Rights and the women’s movements, and used her experience as an African-American woman to enhance both agendas.11

Sources for this page: