The Highlander Folk School

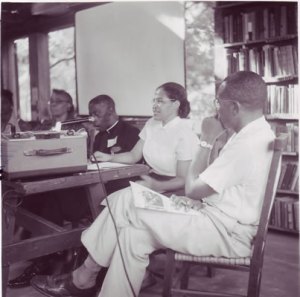

When Septima Clark lost her teaching job in Charleston, she left South Carolina to work at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. At Highlander, Clark continued her passion for adult education, and taught students and visitors from all over the South to read by reciting parts of the U.S. Constitution. The Highlander School held workshops for Civil Rights activists, and trained its students to become community leaders through a range of seminars on topics including union organization, human rights discussions, voter education, and basic skills like money management. Highlander attracted both white and African American Southerners of all education levels to converge and discuss social issues. Attendees also had the privilege of listening to inspiring speakers including Eleanor Roosevelt and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to help spark social activism. Septima’s work at Highlander led to the birth of other citizenship schools across the South.1

Whites in Tennessee resented the Highlander School for championing desegregation efforts, and accused its leaders of having Communist ties. The school had its charter revoked in 1959 for the “illegal sale of liquor,” for providing African Americans with beer since they were barred from purchasing it in town stores. In addition, the Highlander School was accused of violating its non-profit status by selling other items like chewing gum, that African Americans could also not buy elsewhere. The Tennessee Supreme Court refused to appeal the revoked charter.2

Citizenship Schools

Clark worked with her cousin Bernice Robinson as well as Esau Jenkins, a bus driver from Johns Island who shared her passion for adult education, to develop the concept for citizenship schools. In 1957, they opened a citizenship school on Johns Island that specialized in South Carolina election laws and voting. The school focused on literacy so that African Americans could pass the literacy tests to vote following the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.2

Following the success of the Johns Island citizenship school, Clark, Robinson, and Jenkins opened two other citizenship schools on nearby islands. The results were astounding, as 600 African Americans from citizenship schools became registered to vote in Charleston County in the next three years. Their success proliferated as 37 citizenship schools opened on the South Carolina islands and mainland by 1961. Clark explained the founding concept of the schools as: “The basic purpose of the citizenship schools is discovering local community leaders…It is my belief that creative leadership is present in any community and only awaits discovery and development.”3

Sources for this page: